CURED COLOR DEVELOPMENT IN PROCESSED MEATS

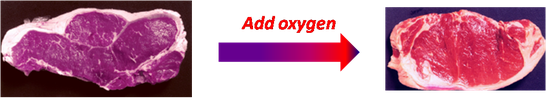

The muscle pigment myoglobin is what gives meat its natural color. When meat is first cut, it has a purple-red color. When the pigment combines with oxygen, oxymyoglobin is formed which is the typical color of fresh meat (bright pink in pork and bright cherry red in beef).

We add nitrite to meat products such as hams and bacon for cured meat color, cured meat aroma and flavor. It is also a powerful antioxidant (controls fat oxidation) and it is a preservative with antimicrobial properties. It specifically controls Clostridium botulinum, Clostridium perfringens and Listeria monocytogenes.

The use of nitrites began prior to the advent of refrigeration when salt was applied to meat for preservation purposes. In salt, there were impurities such as potassium nitrate (salt peter) and sodium nitrate. The presence of the nitrates resulted in a pink color in the meat pigment. However, this was very time consuming.

Science and research through the years resulted in the finding that this slow cured color development was due to the basic meat chemistry of nitrates breaking down to nitrites and ultimately to nitric oxide.

The reaction between nitric oxide and the meat pigment myoglobin results in the uncooked cured meat pigment nitrosomyoglobin.

Today, most processors add the curing compound sodium nitrite to develop cured product; either directly or in the form of a salt/sodium nitrite combination. Adding the curing compound in the form of nitrite gives one more control over the curing process because when using nitrates there is little control over the conversion of nitrate to nitrite. Nitric oxide is a gas so adding it directly in a commercial situation is problematic.

As mentioned above, it is nitric oxide combining with the meat pigment myoglobin to form the cured meat pigment. The conversion from nitrite to nitric oxide can be accelerated with the addition of a catalyst. A catalyst is defined as a substance that speeds up a chemical reaction but is not consumed by it. We can add catalysts such as sodium erythorbate, sodium ascorbate or ascorbic acid. This results in a rapid conversion of nitrite to nitric oxide and the resulting uncooked cured meat pigment nitrosomyoglobin.

Eventually, the uncooked cured meat pigment will form the cured meat compound, nitrosohemochrome when the product is heated. Nitrosohemochrome is a pink colored pigment that is relatively stable. This pink "cured meat" color will continue to be pink when it is cooked as well as if the meat product is cooked multiple times.

Images of the pigment nitrosohemochrome are below.

Pork Beef

In addition to creating the cured meat color, nitrite's antioxidant properties result in the "cured meat" flavor we experience. The antioxidant properties of nitrite also prevent the formation of "warmed-over flavors" typical of reheated cooked meat. Finally, nitrite in cured meats plays a critical safety role as it significantly reduces the chance of botulism and other pathogens previously mentioned. The stability of the nitrosohemochrome pigment in the final cooked product is influenced by oxygen, light and the percent total myoglobin pigment that is converted to nitrosohemochrome. You never convert all of the pigment but rather a percentage of it. The higher the percentage of pigment converted the more stable will be your cured color. This pigment conversion takes time which is why processors often build in a holding period during manufacture between starting the curing reaction and heating.

Processors may hold injected, cured hams for a day or stuffed sausage overnight. Items which are cooked very rapidly, without the holding period, may develop an initial good cured color. However, the color may lack stability under the exposure of light and oxygen. This is of significant concern in sliced ham, bacon and cured sausage products. Consequently, these products are generally packaged using materials that exclude atmospheric oxygen during storage and merchandising.

In conclusion, practice these processing tips to obtain a good, stable meat color:

· Use sodium nitrite (not nitrate)

· Use a catalyst such as sodium erythorbate, sodium ascorbate or ascorbic acid to accelerate the breakdown from nitrite to nitric oxide

· Hold injected product (ham and bacon) for a day or sausage product overnight prior to heat treatment. Holding product helps increase the percentage of pigment converted and to stabilize the pigment

· Package cooked cured products utilizing packaging materials that exclude atmospheric oxygen to prevent color fading

Write a comment